Each of us takes a unique approach to the world; we have things that drive us, energize us, and attract us, and things that drain us or even repel us. In this moment, while we are all navigating an unfamiliar and challenging set of circumstances, these motivations feel especially relevant. Understanding our motivations is also a broader, lifelong topic, however. The motivational predispositions we possess inform the way we experience the world – and they are with us through good times and bad.

Developing a deeper awareness of our motivational drivers can help us with the essential and difficult work of self-regulation: making conscious choices to manage our emotional impulses and respond more objectively (and productively) to life’s challenges.

This was the subject of last week’s webinar, Motivation and Self-Regulation: How Self-Awareness and Observation can Increase our Inner Resilience, delivered by Andrew Rand and David Ringwood, two of MRG’s leading experts in the Individual Directions Inventory™, an assessment tool that helps us illuminate and study motivation. The full presentation is available on-demand here, but you can read the highlights below, as well as Q&A with the experts.

Understanding Motivational Predispositions

What are we talking about when we discuss our motivations – or our “deep drivers”?

A few things to keep in mind:

- Motivational factors originate from the formative years and evolve slowly over time. Many of us can recognize our behavior, but not necessarily our motivations.

- Often we’ll be surprised by our motivations. It’s hard to have an objective view of yourself.

- People will underestimate their most extreme motivations. This is likely because they’ve come to normalize them (“Doesn’t everybody feel like this?”).

- Motivation can conflict with itself. That can create mixed feelings, and emotional confusion.

The motivational predispositions that stem from these drivers are the tendencies we have to react to stimuli in certain ways. Why do I think the way I think, or feel the way I feel? Depending on an individual’s level of introspection, and how much work they have done to increase self-awareness, they will have a different understanding of these motivations and their impact.

How do these motivational predispositions manifest?

Are they good or bad? The short answer: both.

Imagine a few examples:

You are motivated by providing comfort & support.

- The upside: you are likely protective, helpful, and sensitive to others’ needs.

- The downside: you probably find it hard to say “no.”

You are motivated by getting recognition & respect:

- The upside: you are likely to be socially adept, and aware of your impact on others.

- The downside: you may feel forced into things by others, or not able to make decisions for yourself.

These predispositions are not behaviors in themselves, but they certainly influence our behaviors – and these can create self-reinforcing patterns.

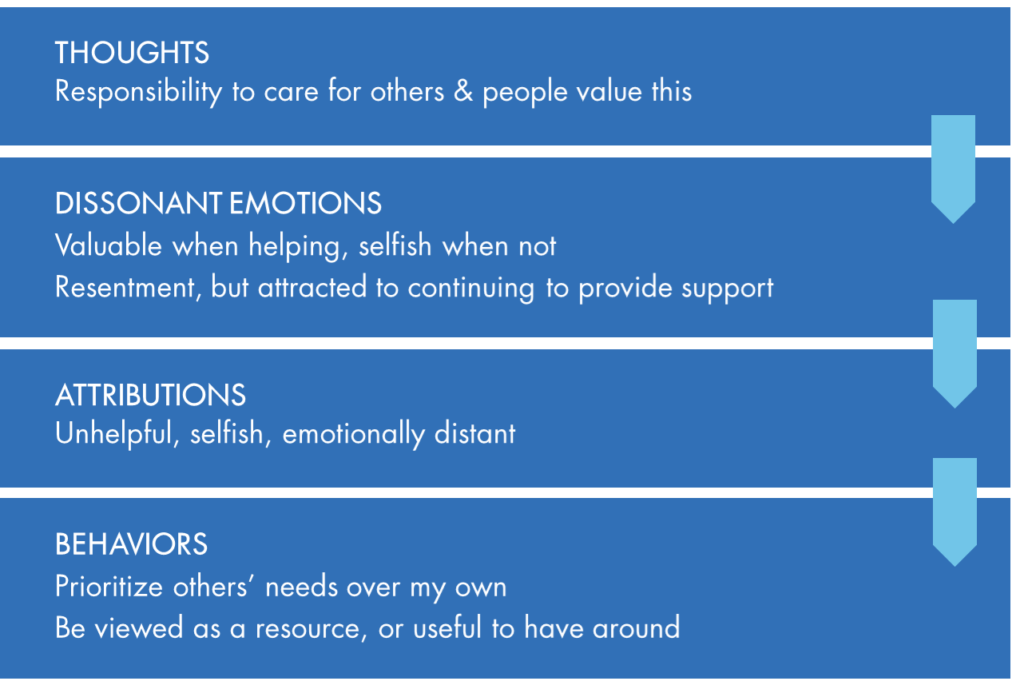

For example, for an individual who is strongly motivated by giving to others may experience the following pattern:

Cycles of Reaction

Drivers aren’t all bad or problematic. They can help us discover what we enjoy, and where we derive satisfaction. But these self-reinforcing patterns do present some risks. Being cognizant of our motivational dispositions and their downsides can help us mitigate these risks, simply by taking the time to recognize them, pause, think, and reflect.

So what steps can we take to harness self-awareness to help us regulate our emotional responses?

Step 1: What am I most sensitive to?

Self-awareness is at the heart of self-regulation. Developing self-awareness is a lifelong process; the Individual Directions Inventory™ is MRG’s tool to support self-awareness by helping to reveal deep motivational patterns. (If you’re unfamiliar with the assessment, learn more here or contact us with questions.)

Whether you use a tool or self-observation, you are trying to understand your biggest triggers (for example, criticism, uncertainty, exclusion, etc.). When you react, you are trying to reflect on how much of your response is based on the facts alone, and how much is based on what we feel or believe about these facts.

Step 2: How do I react?

Observe what happens when you react to these triggers. You may even want to keep a journal. When do these responses happen the most? How does your body respond? What are your emotional and psychological responses? What does your self-talk sound like?

Step 3: What helps alleviate these effects?

Establish the effective strategies to help you break the emotional cycle.

These could include:

- Having a conversation with yourself one week from now. What would you say to your future self about what’s happened, and about your reaction?

- Taking a pause: try to think rationally about your response. If you’re finding that difficult to do, consider distracting yourself with another task, and returning to the situation after you’ve stepped away and can think more clearly.

- Look for evidence: think about similar reactions you have had in the past, and be sure that those lessons inform your current reaction. Is your response evidence-based?

This work is a life-long process. But if you are making progress, you will start to see some positive indicators: a more objective ability to engage in self-observation; a more empowered internal narrative; the ability to win back perspective even after an initially emotional response; and a stronger commitment to yourself.

You can’t serve from an empty vessel. Doing the work to understand your own motivations may seem self-interested. But harnessing this knowledge to empower greater self-regulation doesn’t just benefit you; it benefits those around you, as you can support and respond to them with greater clarity of mind.

For a deeper dive into this topic, watch the one-hour on-demand webinar here.

Questions & Answers

Q: What influence does parental behavior have on motivation?

A: This question lends itself back to the age-old debate of nature versus nurture. What is important to remember is that our motivational predispositions develop during the first 10 to 12 years of life (according to developmental psychology). Parental style and behavior absolutely have an impact on how motivation develops, but it is difficult to answer with any specificity because we don’t really know what % is nature and what % is nurture. But certainly, having an authoritarian parent versus a more democratic parent will influence motivation. Observing a parent respond aggressively or assertively to things versus calm and collected will have an influence. I could go on, but the simple answer is yes there certainly is an influence.

In terms of “issues” or “defense mechanisms”, motivations can certainly develop in the formative years as a survival mechanism. In fact, quite often they are a driving force behind a motivation developing and the ramifications of that motivation are felt throughout life (even though the threat that existed when the motivation developed is no longer present). What’s important to remember is how strong and impactful these motivations can be throughout a person’s life.

Q: What do you make of profiles with a large amount of low scores?

Nothing specific. There isn’t a global conclusion/interpretation that can be made about profiles with a larger number of low scores. You may say that a person has “less places to go” to derive a sense of energy and satisfaction because of a larger number of low scores, but I wouldn’t go much further than that. What would be important is to look at the combination of low scores (in conjunction with high scores) to help with the overall interpretation.

[Follow up question] Is there a correlation between a majority of low scores and depression? Not that I am aware of, and we would need to look at the statistical relationships between IDI and a relevant psychometric that looks at depression (e.g. Beck) to answer that empirically.

Q: If I am High Giving, how do I reconcile thinking of my own needs, but also consider the Christian view to put others’ needs first?

A: I’m not sure I completely understand this question, but two things come to mind. First, it sounds like you may have a higher irreproachability score and a certain portion of your values is centered around putting other’s needs in front of your own. Thus, the relationship between Giving and Irreproachability is something to consider. If your question is referencing guilt about thinking of your own needs instead of always putting others’ needs first, I would evaluate how sensible the emotion of guilt is. Remember, there isn’t anything wrong with thinking about your own needs. It is also commendable to be thinking of others. The balance will be ensuring you satisfy your own needs without violating your value system of helping others, and remembering the two aren’t mutually exclusive (i.e., just because you’re thinking of your own needs doesn’t mean you aren’t thinking of others).

Q: What happens when someone who is motivated to gain recognition and respect also has low EQ? Does some other skill develop to compensate?

A: Not necessarily. Motivation and competence are not the same thing. There are certainly areas of EQ that would help to moderate the effects of needing recognition and validation (e.g. Stress tolerance, flexibility) or to deal with the reactions to same (impulse control) without acting out. The question though is a very important one; what either motivationally or otherwise is available or can be developed by that individual to regulate these intrinsic characteristics?

Q: What role does helping to identify and define emotions for clients (anxiety vs. fear vs. stress, etc.) play to help “peel the onion” on the IDI, as well as emotional regulation and strategies?

A: I have found it helpful to think about and to explore what emotional associations and consequences that accompany different IDI drivers. For example, the Stability driver (higher ranges) might be associated with fear or trepidation, whereas elevated scores on Excelling can drive feelings of impatience, frustration and urgency. Higher ranges on Winning (especially with lower Affiliating scores) can tend towards hostility, whereas higher ranges on Gaining Stature and Receiving can create a dissonant experience of anxiety if those drivers are not satisfied. We can’t make any assumptions though, so I like to ask the coachee how motivational effects show up in their experience.

Q: Can you comment on the relationship between self-awareness and gaining trust and sustaining relationships?

A: That’s a big question. To me the relationship between self-awareness and gaining trust and sustaining relationships is grounded in the ability of the individual to be able to self-observe and to have an objective view of how they are likely to be coming across to others, as this will shape the quality and depth of those relationships. This necessarily requires the individual to also be observant of others (other than through their own natural biases and filters), so that they can calibrate their behavioural choices more sensitively based on what they understand of that other person. What they do in practice is important; there is a big difference between understanding people and making them feel understood, the latter will more meaningfully contribute to deeper and more trustful relationships.

Q: When talking about stress and motivation, how do you reflect on the “threat versus challenge” aspects of stress? In other words, where stress can be motivating?

A: I think that’s a question of extent, and one of the benefits of measuring in 5 percentile increments in terms of outcome measures. There is a point up to which the gravitational pull towards achievement for example is constructive, driving a desire to succeed and to push oneself hard. There is a point after which is might turn into self-punishment for its own sake, the “never good enough” mentality and the easy dismissal of achievements as the individual pursues deferred gratification. One of the questions for me is the extent to which the person recognizes that tipping point, and the advantages and disadvantages that necessarily accompany any motivational profile. Ask those bigger questions about whether these drivers serve the person well, what prices do they pay for same, and whether there are specific drivers that influence the person to the extent that their lose their locus of control.

Q: Considering the cycle of reaction [it was noted that some individuals experience a fast, pronounced reaction; others have a long, slower simmer]. What if the initial reaction is high, but there is also a long lingering effect?

A: This is not uncommon and suggests two things (although this is an oversimplification). It suggests that the trigger event is both single and considerable, or is the effect of multiple sources or the domino effect. The domino effect is where someone gets upset about one thing, they their mood pulls them to see everything in a dark light, they draw in other frustrations or insecurities and this builds its own momentum. The lingering effect in my experience is either down to a lack of coping mechanisms or the multiple cause effects mentioned earlier, as this tends to self-sustain. It is worth looking at some IDI to see if “letting go” might be a topic to explore. This can come in different forms but I’d look at Giving, Belonging, Excelling, Enduring and Stability to begin with.

Q: Do you notice any particular IDI profiles that tend to be more resilient? Or any profile who is less resilient?

A: There are a few scales that certainly can drive greater resilience, but the person can always tell you more than the scores. I’d look at Gaining Stature (lower scores), Enduring (higher scores) and Independence ((higher scores).

If you are curious about resilience, we do have some interesting research on the behavior patterns of resilient leaders – you can download the Best Practice Report here (or MRG Clients can access it directly in the MRG Knowledge Base).

(Are you part of the MRG network? Log into the MRG Knowledge Base once to access other webinars and more than twenty Best Practice Reports, along with the full MRG research library.)

Also, if there’s anything we at MRG can do to help support you or advise you as you transition to more online coaching, training, and facilitation in the coming weeks, please don’t hesitate to reach out. We’re all working through this together (even if we’re apart!).